Some thoughts inspired by the readings for the First Sunday of Lent, Year C

A religious conversion is, for many people, a lot like falling in love. It certainly was in my case, when I completed my own journey from nominally Presbyterian to Evangelical to almost-Anglican to Catholic. Over the course of many years, I came to see how the questions I’d had about my broadly Protestant understanding of Christianity were answered in satisfying ways by the Catholic Church. This intellectual persuasion was necessary for me before I could convert, and it seems to me that this kind of progression should be more common than perhaps it is. But now is not the time for a lengthy discursus on the proper understanding of how reason and faith are related. What’s on my mind as I write this is the more experiential component of my conversion. Attending Mass as a genuine inquirer rather than as a mere spectator just felt different. It felt right. There was something there that I’d never encountered in a Protestant context, even in the very best churches and communities I’d been part of. Eventually, I got to a point where there were no new facts I needed to learn, no new arguments I needed to hear; instead, looking at the same data and at familiar old debates, I started to see them in a new way. Something like a Gestalt shift took place for me. What once looked one way, now appeared quite different.

Again: I fell in love.

I did not, however, have the experience of an ugly breakup. Don’t get me wrong: falling in love with the Catholic faith1 meant that Evangelicalism and I could never get back together. Catholicism wasn’t some temporary fling. We’re for real. It’s permanent. We’re married. But Evangelicalism and I split up on friendly terms.

And oh man is it weird running into my ex.

As I write this, I am on day three of a four-day event on the campus of a conservative Christian college: my son Jake is competing in a speech and debate tournament hosted by Cedarville University, and I’m here with him as a chaperone and judge. [He’s doing great, by the way! You should see his interpretation of C. S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce.] It’s a surreal experience, being immersed in an environment that was once so hyperfamiliar to me, but which I consciously left behind for something else. The feeling can’t be too different from that of catching up with a former girlfriend with whom one had a good but failed relationship. We had something really special once, Evangelicalism and I, but now we’ve grown apart.

The metaphor only extends so far, however. Like many Protestant-to-Catholic converts, I don’t feel like I’ve replaced one faith with another. To use a popular Catholic phrase, I feel like I’ve found “the fullness of the faith.” I didn’t dump Protestantism and take up with someone else. It’s more like I’d been eating at Longhorn and then got invited to a high-end steakhouse. Or like the only music I’d ever been exposed to was performed by high schoolers, and then someone took me to Severance Hall to hear the Cleveland Orchestra.2 Or like the only swimming I knew was in someone’s backyard pool and then I won a trip to an all-inclusive resort where the pool is shaped like a dolphin and there’s a waterfall and a swim-up bar with complimentary drinks. Or… you get the idea. My experience of Catholicism has, on the whole, been the experience of Protestantism fulfilled, Christianity in full flower.

This topic has been on my mind this week not merely because of my trip to Cedarville, but because one of the readings for Mass this Sunday, the first Sunday of Lent, is a passage near and dear to the Protestant heart. Indeed, most Protestants would be comfortable identifying this text as one of the foundations of the Protestant Reformation itself.

Before sharing the passage, let me explain some of its significance from a Protestant point of view. The Catholic Church of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries suffered from serious corruption and institutional abuses of various kinds. I don’t think anyone would dispute this. Among those abuses was the sale of indulgences, used largely to raise money for the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica. This gave the impression that salvation itself is the kind of thing that can be bought for a price, a false and dangerous view intertwined with the authentic Catholic teaching that what we do, and not merely what we believe, plays a role in our salvation. The Reformers eventually became persuaded that the whole package of Catholic ideas and practices was completely bogus. They preached the doctrine of sola fide, declaring that we are saved by “faith alone.” They rebelled against the Catholic Church, arguing that she had rejected the true gospel taught by Sacred Scripture in favor of a literally diabolical heresy.

One of the passages to which Protestants then and now would point in support of sola fide is the same one that appears as the second reading in Catholic Masses this week. It’s from the tenth chapter of St. Paul’s letter to the Romans:

Brothers and sisters:

What does Scripture say?

The word is near you,

in your mouth and in your heart

—that is, the word of faith that we preach—,

for, if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord

and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead,

you will be saved.

For one believes with the heart and so is justified,

and one confesses with the mouth and so is saved.

For the Scripture says,

No one who believes in him will be put to shame.

For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek;

the same Lord is Lord of all,

enriching all who call upon him.

For “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.”

It’s a beautiful passage, and if we’re being honest, I think it’s easy to see why someone might take it as a refutation of the Catholic view that works play a role in our salvation. “One believes with the heart and so is justified” — that sounds pretty straightforward!

Now, there are numerous directions we might go from here. One point worth making quickly concerns the dangers of “proof-texting,” of taking a Bible passage out of its literary and cultural context and using it to make a theological point without attending to the author’s broader argument or the meaning it would have had for its original audience.3 With respect to Romans 10, we could note that St. Paul, in chapter 2 of the very same letter, also writes that God

will render to every man according to his works: to those who by patience in well-doing seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life; but for those who are factious and do not obey the truth, but obey wickedness, there will be wrath and fury.

Looking at this passage, I daresay that an honest reader will admit: it’s easy to see why someone might take it as a refutation of the Protestant view that works play no role whatsoever in our salvation. “He will render to every man according to his works” — that sounds pretty straightforward too!

Obviously, resolving the apparent tension between what St. Paul says in Romans 2 and what he says in Romans 10 would require some pretty serious biblical exegesis. That’s not something I’m going to undertake here. Instead, I want to offer a couple of observations that may, perhaps, function as an olive branch to Protestants who are leery of Catholicism because of their commitment to the doctrine of sola fide.

First, allow me to point out the simple and utterly uncontroversial fact that lies behind this post: Romans 10 is one of the readings at Mass this week. On March 9, 2025, at every Catholic Mass, everywhere in the world, someone will read these words aloud. That’s at least a little bit interesting, isn’t it? Picture the Catholic church closest to your home. This Sunday, a lector is going to stand behind a podium in that building and proclaim a text that is thought by many to disprove Catholicism. He or she will then pause and conclude the reading by saying, “The word of the Lord.” The congregation will respond, “Thanks be to God.”

One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that Catholics are extraordinarily stupid. It might be the case that Romans 10 really does contradict Catholic teaching and that the Church has not only been unable to recognize the contradiction, but she has made the boneheaded mistake of including an inherently Protestant text in her public liturgy, then doubling down on it by declaring it “the word of the Lord.” That could be the case, I suppose, but it hardly seems likely. A much more plausible hypothesis is that those who decided to include Romans 10 in the Mass readings believed that it is actually compatible with the Catholic understanding of salvation.

Space precludes all but the briefest of descriptions of the difference between Protestant and Catholic understandings of how we are saved by God.4 For present purposes, the most important difference is that Protestants—certainly, contemporary American Evangelicals—see salvation as a one-time event. Either you have saving faith in Christ, or you don’t. Either you have trusted him, or you haven’t. Either you are saved, or you are not. Period. Catholics, on the other hand, see salvation as a process. The Catholic answer to the question, “Are you saved?” is “I have been saved, I am being saved, and I hope to be saved.” This is an answer that makes no sense given standard Protestant categories, but it is the correct answer given a Catholic understanding of the New Testament. If you want more details on this from me, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait for another post. (In the meantime, you can learn a lot from The Catechism of the Catholic Church or this essay.)

What I want to emphasize here is that the debate between Catholic and Protestant theologians cannot be settled merely by pointing to scriptural texts that are supportive of, or problematic for, one side or the other. Catholics—even if mistaken!—see ourselves as practicing authentically biblical faith. The inclusion of Romans 10 in the Mass readings is striking evidence of this fact.

The other main thing I want to point out about Romans 10 is that it doesn’t settle one of the big questions about faith and works that Protestants argue about with each other. If you hang out for a while with theologically-minded Evangelicals, one of the issues you’ll eventually hear them debate is the “Lordship Salvation” controversy: given the Protestant view that we are saved by faith alone, there is a question as to whether a person is made right with God merely by having faith in Christ as savior or if it is necessary also to trust Christ as Lord, to intend to follow him and be obedient to him.

Now, given my unwillingness to get into the weeds with respect to the Protestant-versus-Catholic question, you can rest assured that I’m not even going to touch a Protestant-versus-Protestant debate. But notice this. Even within the Protestant realm, we have a spectrum of possible views about the relationship between faith and works. At one end of the spectrum are those who say that belief and behavior are two completely different things: you can be saved without repenting of your sins or making any lifestyle changes at all. At the other end of the spectrum are those who say that good works are a necessary and inevitable outcome of saving faith, evidence of the inward regeneration that begins at the moment of salvation. The Catholic view is that we are invited to cooperate with God’s grace in our lives. The initiative is his, and it is by his grace and his work in our hearts that we are able to, in St. Paul’s words, “work out [our] own salvation with fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12).

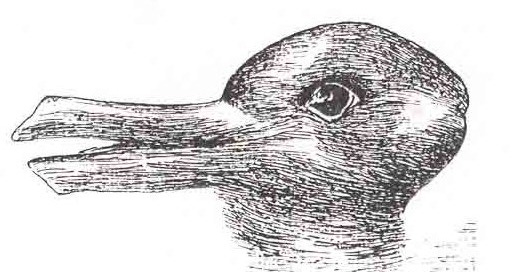

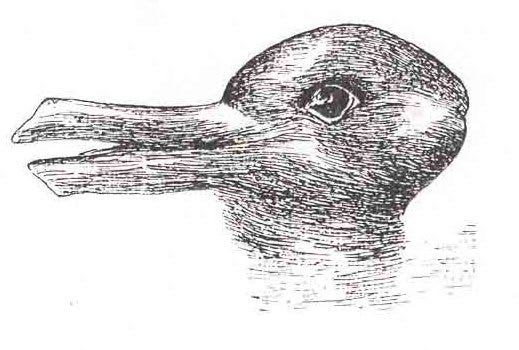

I can say with confidence that many Protestants hold a view of Catholic teaching that is really just a caricature, and an absurd one, at that. They think that embracing Catholicism means believing that we do good works in a frenetic endeavor to earn God’s favor, hoping that the sheer volume of good things we do will be sufficient somehow to offset our sin, so that God will owe it to us to admit us to heaven when we die. This is simply and utterly false. The Catholic view can be expressed pithily in the words of St. Paul we saw earlier: “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.” When we call on his name—when we come to Jesus in faith—we enter into a loving relationship with him, a process of renewal and transformation, a journey whose destination is attaining “to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ.” (That’s St. Paul again, by the way: Ephesians 4:13.) If I may be so bold, this view belongs not in a separate category from the Protestant ideas described above, but as another point on the same spectrum. It’s not the dynamic of the duck/rabbit image I shared earlier, but it’s not too far distant, either.

All of this is just the tip of a very large iceberg, of course. In general I don’t like to gloss over differences or pretend they don’t exist. And the differences between Catholicism and Protestantism are real. We can’t embrace both, not completely. But some of the gaps are narrower than many people believe. When it comes to the issue that was arguably at the center of the Protestant Reformation itself, the gap turns out to be quite narrow indeed. Come to Mass this Sunday and hear for yourself.

I can only imagine how many hackles a phrase like this would have raised for me in my pre-Catholic days, so let me hasten to add that it would be more accurate to say that I fell in love afresh with Christ through his unique presence in the Catholic Church. But that raises an entirely new set of complicated issues that I don’t want to talk about right now, so let me have my metaphor, okay?

I chose this example partly because I’m a homer, partly because most people who read these posts live in northeast Ohio and will appreciate the reference, and mostly because it gives me a chance to note that the Cleveland Orchestra is among the world’s top-ranked orchestras, and I, for one, find it endlessly amusing that orchestras are ranked.

For anyone interested in the meaning this passage would have had for Paul’s original audience, this short essay is worth a look.

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that there is no one uniquely “Protestant” view on this, but we can ignore that complication here.